Although, with just eight million people Tajikistan stays far behind Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan in terms of population size in Central Asia, the country has the highest birth growth rate in the region. Ironically, Dushanbe officials are the only one in the region introduced birth control recommendations advising couples not to have too much children. CAAN goes in-depth into family life in Tajikistan together with Dr. Cynthia Buckley, Professor of Sociology at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Professor Buckley researched birth timing and contraceptive use in Tajikistan and throughout of this interview quotes Tajik women bringing real life examples.

Do you have any data on birth rate in Tajikistan and its growth in recent years?

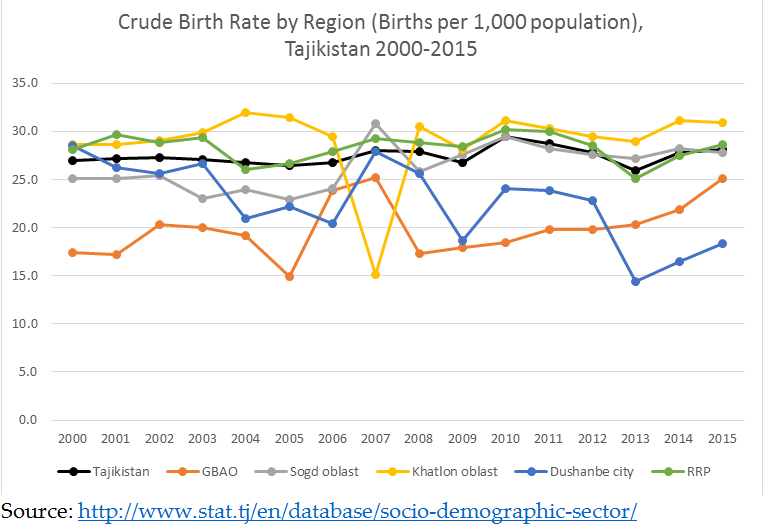

The Crude Birth Rate (CBR) refers to number of annual births per 1,000 population. Data from the Agency on Statistics of the Republic of Tajikistan indicate that while regional measures have varied, the national trend has remained fairly constant at between 26 and 28 births per 1,000 population over the past 15 years. This is well above the global average of 19.2 (2015). Still, official Tajik data report lower CBRs than the World Bank for the country. World Bank date indicate CBRs between 28.9 and 30.9 for the years 2000-2015. This discrepancy may reflect a difference in the estimated population out migration during this period.

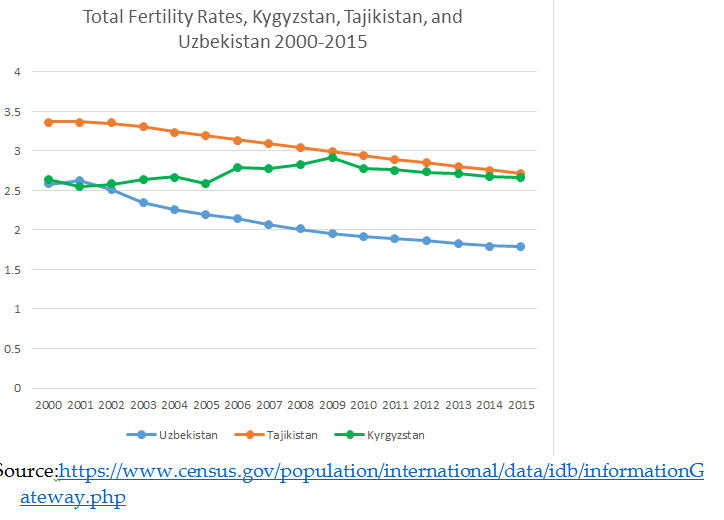

A more often employed measure of fertility, the Total Fertility Rate (TFR) is a more precise estimate of fertility, indicating the average number of children a women would have if subject to the schedule of age specific birth rates in a given year. Based upon data from the US Census International Data base, this hypothetical cohort measure has declined markedly in Tajikistan between 2000 and 2015, from 3.4 children on average to 2.7 children. At the time of independence in 1991, the TFR was 5.2. TFRs can be misleading, as they do not reflect the experiences of actual cohorts of women as they move through the reproductive ages.

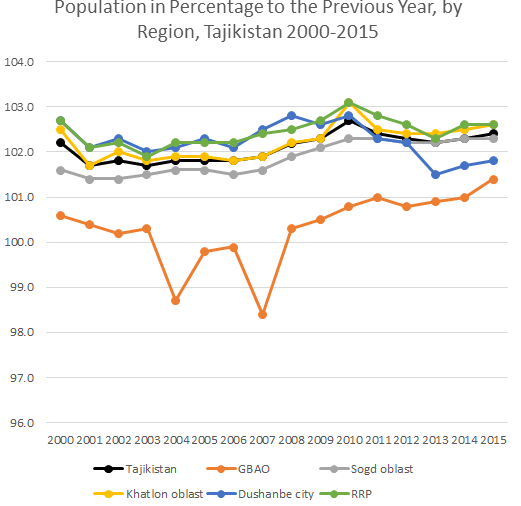

Still, the past 15 years, and perhaps even since independent in 1991, fertility in Tajikistan has translated into healthy rates of annual population increase across the country, even though the Badakhshon region has experienced recent years of population shrinkage.

Tajikistan has the highest birth growth rate in Central Asia, while is the only country in the region which introduced the birth control recommendations officially. Why the state policy does not work here?

I believe the state law has worked. Due to national policies and international assistance, contraceptive use rates have risen dramatically. My research indicates that medical professionals have played a huge role in encouraging women to use contraception to increase the period between births (spacing) and to end child bearing (stopping), with 70% or more of all age groups over 20 years of age reporting that they have heard of modern contraceptive methods. More than half of all married women with at least one child have some intention to use contraception. Both spacing and stopping have led to smaller family size. In terms of Central Asian comparisons, the decline in TFR in Uzbekistan is particularly steep, but Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have very similar TFRs.

What is the normal family size in the country, what is the normal number of children? Has the perception of people about the normal number of children in a family changed and if yes or no, why?

Is any family “normal”? The TFR, which is an estimate of the total number of children a women is likely to bear, shows a clear decline in family size in Tajikistan. Marriage remains nearly universal, and there is a strong preference to begin having children rapidly after marriage. Families of three and four children, rather than six or seven, are much more common for Tajikistan today. Preferences vary by region, with rural families expressing the desire for more children in comparison to urban, and residents in the capital city expressing a small number of “ideal” children for a family in comparison to regions outside the capital.

Across the globe, we find that once populations gain knowledge of and access to contraception, family sizes rarely, if ever, return to the levels common before contraception. Three factors tend to make declines in fertility permanent. First, the decline reflects a tendency towards greater investments in children (education, goods, services, etc.), which can decrease the number of children desired. Second the decline reflects an understanding of the importance of birth spacing for the health of mothers and children. Lastly, in most countries of the world, the decline in fertility is linked to an increase in the status of women, including rising education and professional advancement which makes a return to very high fertility unlikely. In Tajikistan, the first two factors are clearly at work. The third remains a bit difficult to assess, and certainly worthy of further study.

What impact has desire to immediately have a baby right after the marriage to families?

“Young families should give birth as soon as possible. They do not need the information on contraceptives. None of the mothers or mothers-in-law, and especially the husbands, will allow a young bride to use contraceptives”.

“It is better to give birth right away. Doctors will not discuss contraceptives with women who have not given birth yet. Medical staff will talk about that after childbirth or 3 to 4 years after the wedding”.

“After childbirth, the medical staff of maternity hospitals will discuss the topics of family planning and contraception. That is enough, as it should be”.

One element has to do with pressures from their mother-in-law, who often wishes grandchildren right away. Linked to this is the popular perception that wives should “prove” their fertility early in the marriage.

These culturally based pressures interact with beliefs that using contraceptives may lead to infertility, and therefore should only be considered after the first, or second, birth.

Preliminary analyses do indicate that women are less likely to use contraception for spacing if the first child is female. This might mean that the risk of infertility is less of a barrier after the birth of at least one son, but requires further study.

There is some evidence that these factors encouraging early first birth are increasing. Younger women in Tajikistan tend to bear their first child more often within 12 months of marriage.

According to the 2012 Tajik DHS, 43% of women aged 25-29 had their first birth within the first 12 months of marriage, while only 35.3% of women 40-44 had children in the first year of marriage.

Focus group data illustrates how the maintenance of early marriage in Tajikistan is inextricably linked to the strong social expectations of a first birth soon after the wedding.

This exchange (the column in the right) among married women in the 30s in a focus group reflects the sentiment of the majority of respondents in the study.

In last two decades the international community spent millions of USD to introduce the culture of use of contraceptives in the country, and now, for example, pills are disseminated free of charge (and free of corrupted sale too) in hospitals. Do we have other examples of success of the contraceptive use campaign? For example, is there any cultural change in planning parenthood?

From our focus groups, we can conclude that for women in Tajikistan, the improvements in reproductive health are important and meaningful.

In addition to family planning, women’s awareness of sexual health issues and HIV and AIDS also shows marked improvement. Sadly, most of the additional information seems to influence the knowledge level of marriage women only, which points to the exclusion of the young and unmarried.

Did the number of abortions among married women increased? What makes them to go and do an abortion and to what extend this service is affordable culturally and financially? I mean, do we still have a lot of “unplanned and unwanted babies” born because of some obstacles to abortion desire of mothers?

Tajik official data report a rapid decline in abortion use rates, falling from 14.8 abortions on average, per 1000 women in the reproductive ages of 15-49, to just 7.5 between 2000 and 2015. This decline in abortion utilization reflects broader knowledge and use of contraceptives. In our study, women mentioned the importance of seeking abortions very early in a pregnancy (prior to the quickening of the fetus), reflecting some stigma to abortion use later in the pregnancy.

Tajikistan roddoms (maternity hospitals) are known for horrible services and corruption. Is there any effort by the government or the international community to address the issue?

There are some programs to improve hospital care and conditions, and make the registration of births easier and more comprehensive. Still, women’s health issues are not really a clear priority, so I suspect that the birthing hospitals may continue to face troubles with infrastructure, staffing, and funding.